Meeting Antal by Nick Mankovich

I travel. It suits me.

As my family knows, when faced with helping arrange my mother’s 90th year celebration, I chose to assemble family pictures for presentation and memory. This assemblage evolved into some family memory books – picture and prose to tell some stories. One of these books, A Mankovich and Petrick Family History – What is remembered from a family’s collection, turned into a major project that continues to engage me. I have come to cherish learning and retelling these family stories and connecting to the history and culture that anchors them.

Among the photographs from my Aunt Irene that made their way into the book was one of an attractive woman and her two children – the boy in a late 1930’s Hungarian nationalistic uniform. My aunt told me this was the wife and children of Antal Mankovič – my grandfather Paul’s brother. He lived in Budapest and was a teacher. Somewhere along the way I learned that this family had moved to Sweden. Later my third cousin Geza confirmed that his father had said they were living in Stockholm.

During the gathering of stories for the book, I found new pleasure in talking to relatives, hearing their stories, and sharing their thoughts. Because my great-great grandfather had 12 children, an unusual name, and procreative sons and grandsons, I can locate relatives.

There is a special quality to meeting and conversing with found relatives. It is curious to hear and see familiar ways of speaking, thinking, and even moving in someone who was a total stranger moments before. An odd and calming kind of joy comes in realizing that what you are began long before your birth and will go on long after your death.

Thanks to Geza’s contacting my brother John, I have met and enjoyed the company of the families of my third cousins – another Rev. Antal link. Geza F and I have begun to collaborate on genealogy. I have also met my young double-second cousin, Tomáš H, during a few-days’ trip to Brussels.

In the spirit of finding new relatives and with the prospect of getting new stories, I did a little research to discover an entry in the Swedish white pages.

Since my work has me spending many hours a day talking to people in Europe, I automatically dialed the mobile phone listed, but received only voicemail. I left a message but never had a response. So I filed away his address as a potential place to visit if I ever found myself near the town. In the meantime, bits of research accumulated. Maps showed his apartment near the center of the town. Membership lists showed that someone with my last name was an architect, belonging to a Swedish Architect Association. There were references to a trust in his name in Swedish but I could not make any sense of that. Its address was the same.

Finally, I had business in December 2009 with the Swedish government’s Medical Products Agency in Upssala. I arrived via Amsterdam to Arlanda in the early morning of December 10, and from there took the express train to the town, where a taxi took me to the address. This small street ran directly toward sea. The apartment block at the address was about 200m from the harbor. The building was well-secured with a formidable pair of doors and a keypad for entry. The front was devoid of any kind of tenant list and there was no means to ring the occupants. The door was locked solid and, in the late morning damp, no traffic came in or out.

I looked up and down the street, a quiet residential area with almost no activity. I noticed a small brightly colored flag hanging above one door across the street, its graphics and Swedish providing me no hint. Nonetheless, it looked vaguely commercial. I went down the steps and saw, through the door glass, an open room with a counter that looked a bit like a waiting room. I entered.

Immediately, I knew the business: I encountered, as a curtain, the aroma of wet dog. A young man and woman peered at me over a partition in the back. I was in a day care center for the working dog set. The young man and woman standing among a dozen dogs greeted me and said that they spoke a little English. So I asked if they could help me in a little adventure. I explained that I was visiting Sweden and was trying to locate a long-lost relative who might have moved to this town in 1939 or so. My dilemma was that I located his flat but could not enter the building. My two accomplices conversed a bit and the woman volunteered to go across the street and try to use common entry codes to break into the building. Meanwhile, I stayed with her colleague and a telephone where, based on my web search listing, he managed to extract a new phone number from directory assistance.

The woman returned, unsuccessful with her break-in, and proceeded to dial the number we had found. The phone was answered and she passed it to me.

Antal ?

Yes.

Do you speak English?

A little.

I am Nick Mankovich – a relative from America.

Slowly.

I am…

You…are…Nick Mankovits…from…Amerika.

I am the great-grandson of your grandfather Kornel Mankovits.

Slowly.

My father is Paul. My father’s father was Paul. His father was Kornél.

My grandfather Kornél.

Yes. I am here in town.

I am across the street from your apartment and wondered if we could meet.

Slowly.

I am in front of your building. Can we meet?

You are here?

Yes.

At this point I started walking outside with the telephone, my accomplices watching with interest this break in their doggy-day.

I am on the street – can you see me from your window?

Wait – I put down telephone. I go to the window. I am looking.

I looked up at the 6-story window front and waved an arm, still clutching the borrowed phone. I could see nothing at the windows; the sky glare was too bright on the glass. I hung up the phone, thanked my new friends, and said I would meet my relative at the door. I went to the front door of the building. Nobody appeared. I went back to the street and stood directly across the street from the windows and made as if to take flight. There, at the 3rd floor window I saw a round-faced, white-haired man peering and bobbing side to side as if struggling to see through the glass.

I thought he saw me so I returned to the front door. There, after 10 long minutes, a man with a single crutch appeared at the top of the steep entry hall stairs. He was short and heavy set with a round, age-spotted face. I have never seen a shape so similar to my father’s own, although he was physically tentative and frail beyond my final impressions of my father. He made his way slowly and painfully down the stairs in his hospital slippers and, with difficulty, opened the door.

Hello

Hello, I am Nick Mankovich, are you Antal?

Yes.

Kezét csókolom. It is a pleasure to meet you.

Do you speak Hungarian?

No. Only words like “Nem szeretem” and “gyerekek” and “köszönöm szépen!”

You are my second cousin?

Yes. Great-grandson of Kornél.

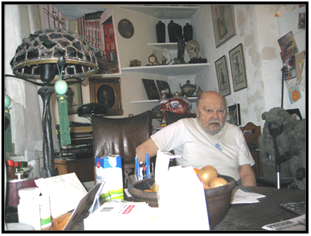

After helping him with a slipper that had escaped his foot, we proceeded carefully up the stairs and up the elevator to his flat. He asked me in and invited me to sit in the kitchen. The apartment was packed with art and artifacts from China. An 8 foot verdigris crane greeted us as we opened the front door. Chinese watercolors were on the wall. Elegantly crafted Chinese cabinetry served as the entry hall table.

In the kitchen, all available wall space was covered with clipped photographs of classical art. The ceiling was adorned with 8 tiffany-style hanging lamps, and a large lithograph of ancient Rome was poised above the small kitchen table. The refrigerator was plastered with children’s crayon drawings inscribed to Anti. Everywhere there were artifacts from China: two grey granite Fu Dogs stood atop wooden pedestals watching our conversation, and Chinese graduated domed bells hung near the kitchen entrance.

We chatted as best we could. I brought out a copy of the Mankovich book, turned to the picture of him as a 10 year old boy in 1937 and asked

You?

Yes, yes (smile) and my mother and my sister.

We then spent about 30 minutes looking at pictures of his family, each time pointing to his father, his aunt, his uncle, his grandfather, his grandmother. He recalled the relative’s name Zima and recognized his Aunt Archika as well as the few photographs of his Uncle Akós.

I drew a small family tree showing Kornél, his father, Antal, and him alongside myself, father, and grandfather.

We are second cousins?

Actually, we are first cousins once removed: that is the way we say it in English. You are my father’s first cousin.

He carefully inspected the caption on each photograph of him or his father, his mother, his grandparents and aunts and uncles. He held the book close to his face to see every person and read every word of the captions. He saw the picture of his father in front of his Budapest flat and the scribbled Hungarian note stating that he is standing in front of the slapdash repair of the 1948 bomb damage.

What means “slapdash?”

Ah… do you know “doma robensis?”

No

It means quickly and poorly put together.

Ah. I do not hear good and I do not see well.

Did you do all this?

I collected the photographs and stories of others, like you, in the family.

Did you do the research?

Yes.

It is very good.

I moved through the book stopping on father and mother, uncles and aunts. We confirmed each picture and, in turn, he closely read, studied, and apparently translated each caption.

|

What in fact makes people who are morally unenlightened upset by the experience of physical distress is their failure to acquire the habit of contentment with the spirit. They have instead been preoccupied with the body. That is why a man of noble and enlightened character separates body from spirit and has just as much to do with the former, the frail and complaining part of our nature, as is necessary and no more, and a lot to do with the better, the divine element.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Letter LXXVIII |

When did you move to here?

1956 we left Budapest. I am 81 now.

You were an architect?

Yes.

Are there other Mankovits’ in Sweden?

Yes, my daughter.

And others?

No, we are the last Mankovits. The end. She has no children.

Why did you come here?

What city are we in now?

Silence and inspection.

What is your daughter’s name?

M.

M Mankovits.

Yes.

Do you have any photographs of family?

Yes.

Can I see any of them?

Oh, I do not know where they are…

If you do find them, I would be interested in any copies that you could make of them. I will write to you and maybe you or your daughter can send them.

You are my second cousin?

Yes.

I saw no photographs of family but I only visited the entrance and kitchen. When we first entered, he waved me away from the living room because the kitchen had space to sit and chat.

Forty-five minutes passed in our halting conversation. His memories were not clear and most questions could not be answered. A few more minutes passed and I gently said that I must be going to my business meeting.

Here is my card and I will write my home address and telephone number on the back.

Good.

Thank you for coming all the way downstairs to meet me and for your kind invitation into your home. I am very, very happy to have met you.

I am also happy to see you.

I shook his hand and left as he closed the door behind me. I went down the spiral stairs back to the street. I crossed and visited my two canine caretaker friends. I thanked them again for their help and related that, indeed, he was my long-lost cousin and that we had spent a very good time together.

Then, steeped in nostalgia, I ambled down the two and half blocks to the harbor and strolled back through Stockholm’s busy streets, reconnecting gradually with the twenty-first century. In spite of rain and 2-degree Celsius weather, the noon-time crowd was large and small canvas booths were set up to sell Christmas goods and food. I smiled at the Polish food booth where fresh pierogi were browning on a grill. We live everywhere and anywhere and make our lives.

Overall, a delightful morning!